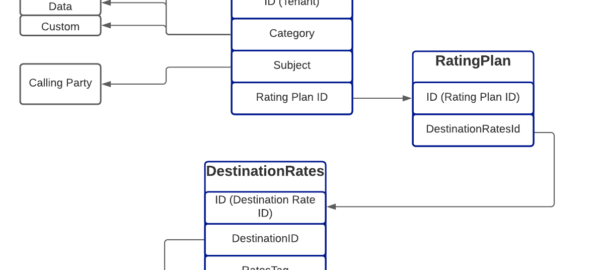

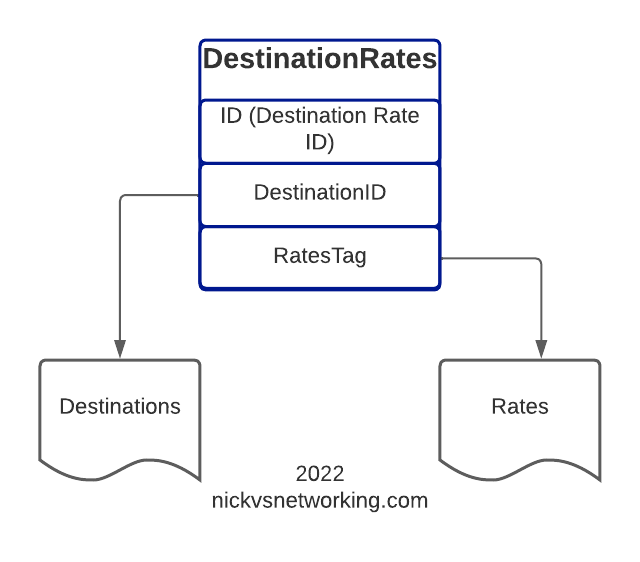

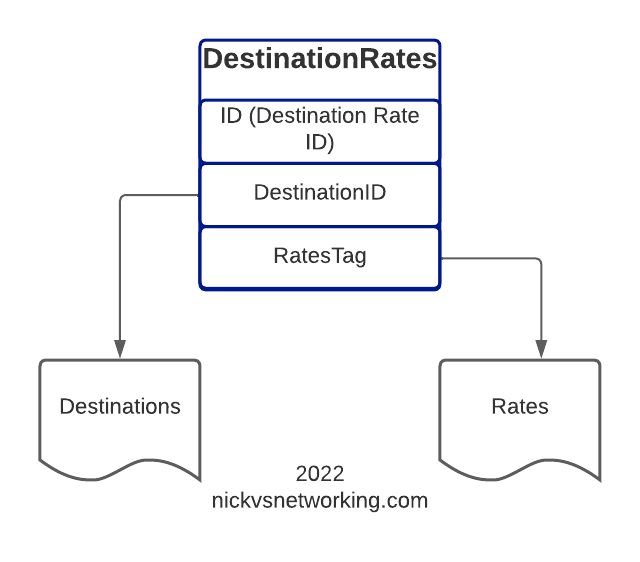

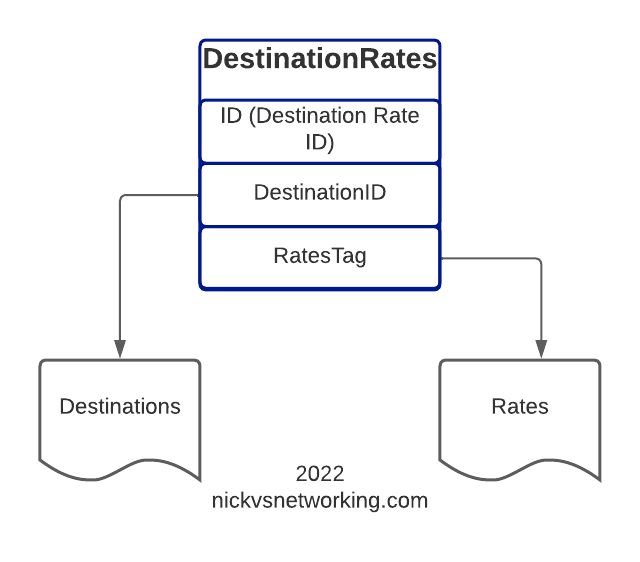

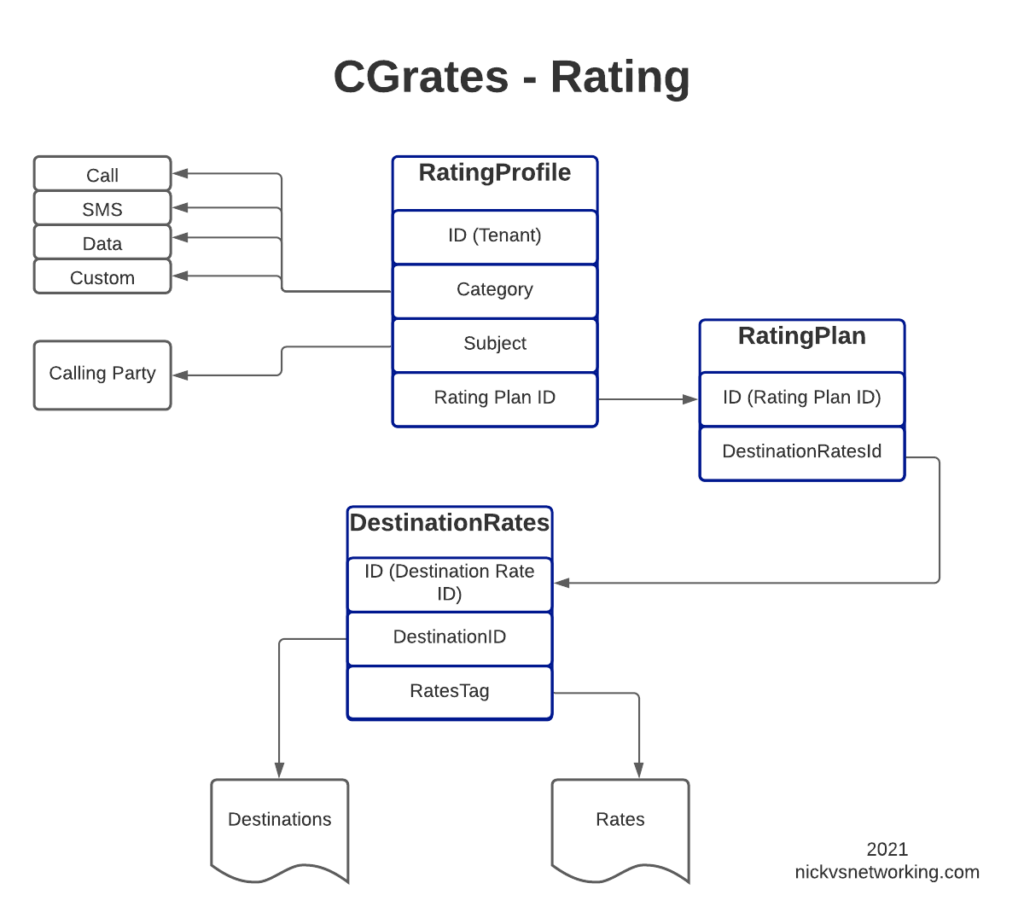

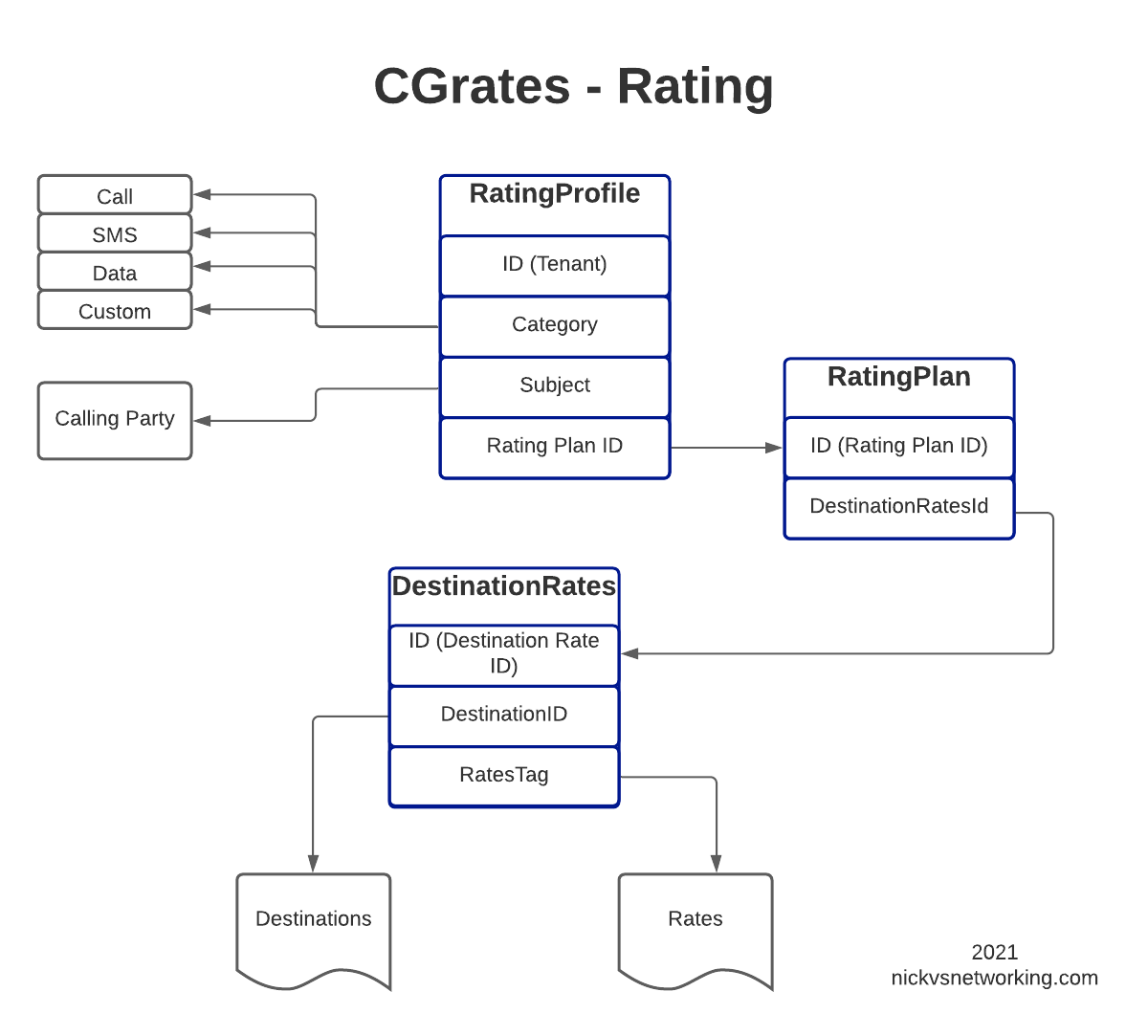

In our last post we introduced the CGrateS API and we used it to add Rates, Destinations and define DestinationRates.

In this post, we’ll create the RatingPlan that references the DestinationRate we just defined, and the RatingProfile that references the RatingPlan, and then, as the cherry on top – We’ll rate some calls.

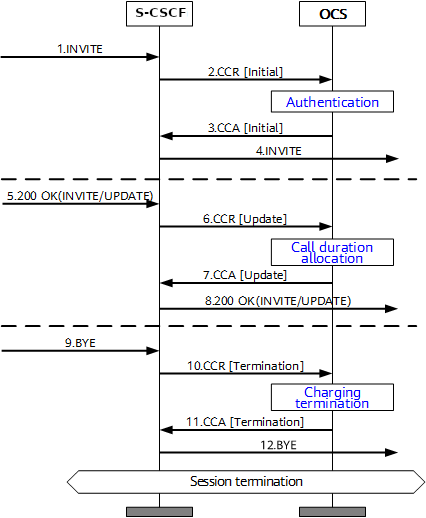

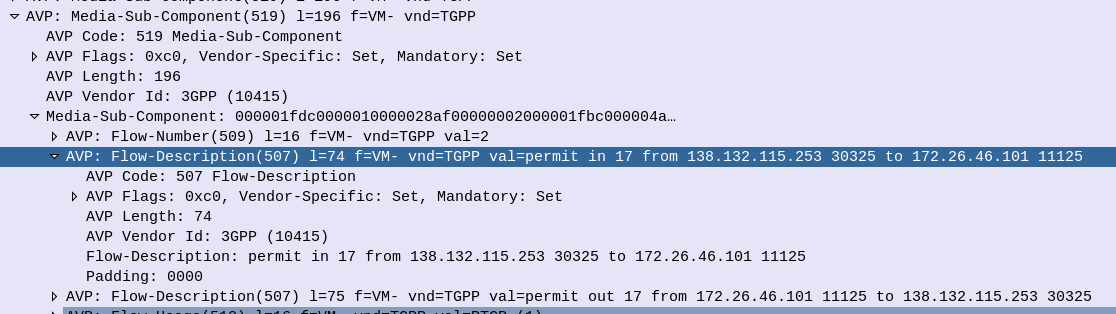

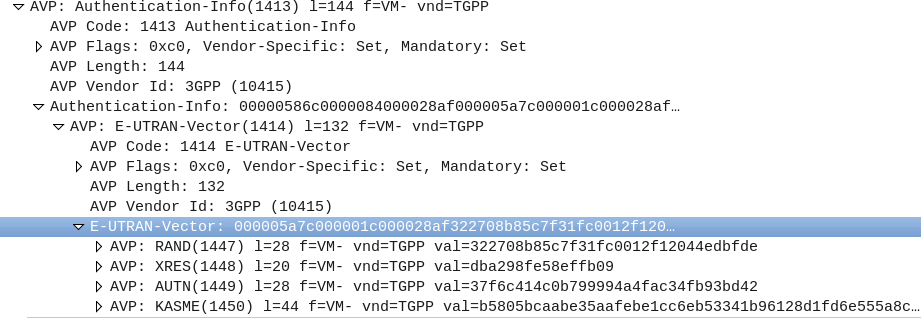

For anyone looking at the above diagram for the first time, you might be inclined to ask why what is the purpose of having all these layers?

This layered architecture allows all sorts of flexibility, that we wouldn’t otherwise have, for example, we can have multiple RatingPlans defined for the same Destinations, to allow us to have different Products defined, with different destinations and costs.

Likewise we can have multiple RatingProfiles assigned for the same destinations to allow us to generate multiple CDRs for each call, for example a CDR to bill the customer with and a CDR with our wholesale cost.

All this flexibility is enabled by the layered architecture.

Define RatingPlan

Picking up where we left off having just defined the DestinationRate, we’ll need to create a RatingPlan and link it to the DestinationRate, so let’s check on our DestinationRates:

print("GetTPRatingProfileIds: ")

TPRatingProfileIds = CGRateS_Obj.SendData({"jsonrpc": "2.0", "method": "ApierV1.GetRatingProfileIDs", "params": [{"TPid": "cgrates.org"}]})

print("TPRatingProfileIds: ")

pprint.pprint(TPRatingProfileIds)From the output we can see we’ve got the DestinationRate defined, there’s a lot of info returned (I’ve left out most of it), but you can see the Destination, and the Rate associated with it is returned:

OrderedDict([('id', 1),

('result',

OrderedDict([('TPid', 'cgrates.org'),

('ID', 'DestinationRate_AU'),

('DestinationRates',

[OrderedDict([('DestinationId', 'Dest_AU_Fixed'),

('RateId', 'Rate_AU_Fixed_Rate_1'),

('Rate', None),

('RoundingMethod', '*up'),

('RoundingDecimals', 4),

('MaxCost', 0),

('MaxCostStrategy', '')]),

OrderedDict([('DestinationId', 'Dest_AU_Mobile'),

('RateId', 'Rate_AU_Mobile_Rate_1'),

('Rate', None),

...

So after confirming that our DestinationRates are there, we’ll create a RatingPlan to reference it, for this we’ll use the APIerSv1.SetTPRatingPlan API call.

TPRatingPlans = CGRateS_Obj.SendData({

"id": 3,

"method": "APIerSv1.SetTPRatingPlan",

"params": [

{

"TPid": "cgrates.org",

"ID": "RatingPlan_VoiceCalls",

"RatingPlanBindings": [

{

"DestinationRatesId": "DestinationRate_AU",

"TimingId": "*any",

"Weight": 10

}

]

}

]

})

RatingPlan_VoiceCalls = CGRateS_Obj.SendData(

{"jsonrpc": "2.0", "method": "ApierV1.GetTPRatingPlanIds", "params": [{"TPid": "cgrates.org"}]})

print("RatingPlan_VoiceCalls: ")

pprint.pprint(RatingPlan_VoiceCalls)

print("\n\n\n")In our basic example, this really just glues the DestinationRate_AU object to RatingPlan_VoiceCalls.

It’s worth noting that you can use a RatingPlan to link to multiple DestinationRates, for example, we might want to have a different RatingPlan for each region / country, we can do that pretty easily too, in the below example I’ve referenced other Destination Rates (You’d go about defining the DestinationRates for these other destinations / rates the same way as we did in the last example).

{

"id": 3,

"method": "APIerSv1.SetTPRatingPlan",

"params": [

{

"TPid": "cgrates.org",

"ID": "RatingPlan_VoiceCalls",

"RatingPlanBindings": [

{

"DestinationRatesId": "DestinationRate_USA",

"TimingId": "*any",

"Weight": 10

},

"DestinationRatesId": "DestinationRate_UK",

"TimingId": "*any",

"Weight": 10

},

"DestinationRatesId": "DestinationRate_AU",

"TimingId": "*any",

"Weight": 10

},

...

One last step before we can test this all end-to-end, and that’s to link the RatingPlan we just defined with a RatingProfile.

StorDB & DataDB

Psych! Before we do that, I’m going to subject you to learning about backends for a while.

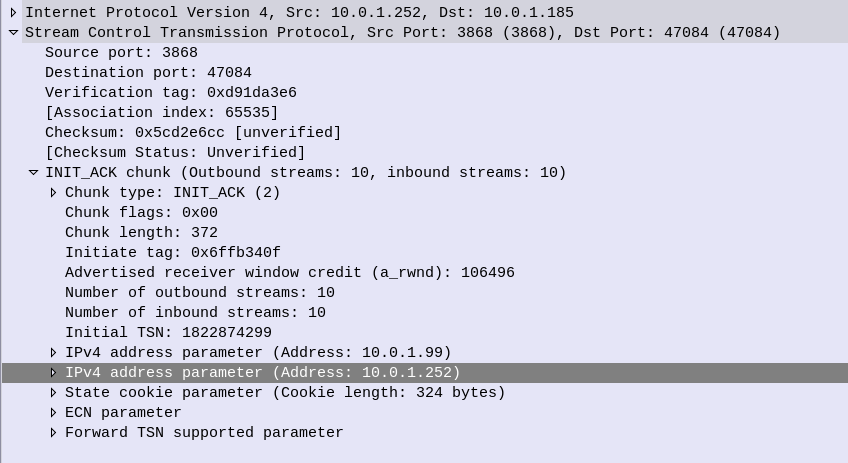

So far we’ve skirted around CGrateS architecture, but this is something we need to know for now.

To keep everything fast, a lot of data is cached in what is called a DataDB (if you’ve followed since part 1, then your DataDB is Redis, but there are other options).

To keep everything together, databases are used for storage, called StorDB (in our case we are using MySQL, but again, we can have other options) but calls to this database are minimal to keep the system fast.

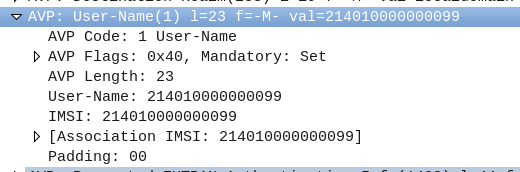

If you’re an astute reader, you may have noticed many of our API calls have TP in method name, if the API call has TP in the name, it is storing it in the StoreDB, if it doesn’t, it means it’s storing it only in DataDB.

Why does this matter? Well, let’s look a little more closely and it will become clear:

ApierV1.SetRatingProfile will set the data only in DataDB (Redis), because it’s in the DataDB the change will take effect immediately.

ApierV1.SetTPRatingProfile will set the data only in StoreDB (MySQL), it will not take effect until it is copied from the database (StoreDB) to the cache (DataDB).

To do this we need to run:

cgr-console "load_tp_from_stordb Tpid=\"cgrates.org\" Cleanup=true Validate=true DisableDestinations=false"

Which pulls the data from the database into the cache, as you may have guessed there’s also an API call for this:

{"method":"APIerSv1.LoadTariffPlanFromStorDb","params":[{"TPid":"cgrates.org","DryRun":False,"Validate":True,"APIOpts":None,"Caching":None}],"id":0}

After we define the RatingPlan, we need to run this command prior to creating the RatingProfile, so it has something to reference, so we’ll do that by adding:

print(CGRateS_Obj.SendData({"method":"APIerSv1.LoadTariffPlanFromStorDb","params":[{"TPid":"cgrates.org","DryRun":False,"Validate":True,"APIOpts":None,"Caching":None}],"id":0}))Now, on with the show!

Defining a RatingProfile

The last piece of the puzzle to define is the RatingProfile.

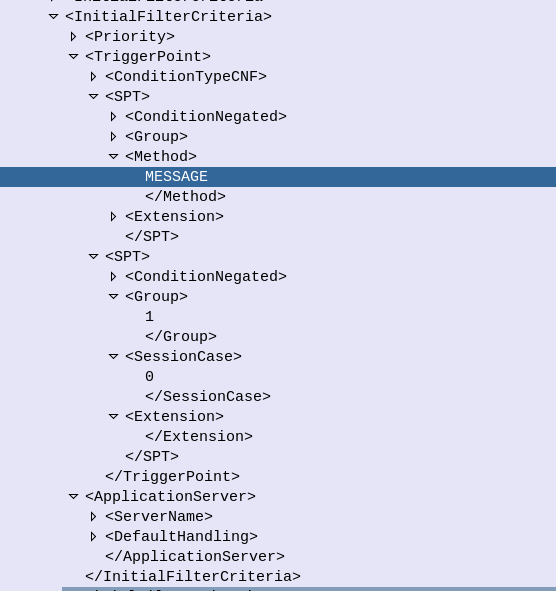

We define a few key things in the rating profile:

- The Tenant – CGrateS is multitenant out of the box (in our case we’ve used tenant named “cgrates.org“, but you could have different tenants for different customers).

- The Category – As we covered in the first post, CGrateS can bill voice calls, SMS, MMS & Data consumption, in this scenario we’re billing calls so we have the value set to *call, but we’ve got many other options. We can use Category to link what RatingPlan is used, for example we might want to offer a premium voice service with guaranteed CLI rates, using a different RatingPlan that charges more per call, or maybe we’re doing mobile and we want a different RatingPlan for use when Roaming, we can use Category to switch that.

- The Subject – This is loosely the Source / Calling Party; in our case we’re using a wildcard value *any which will match any Subject

- The RatingPlanActivations list the RatingPlanIds of the RatingPlans this RatingProfile uses

So let’s take a look at what we’d run to add this:

#Reload data from StorDB

print(CGRateS_Obj.SendData({"method":"APIerSv1.LoadTariffPlanFromStorDb","params":[{"TPid":"cgrates.org","DryRun":False,"Validate":True,"APIOpts":None,"Caching":None}],"id":0}))

#Create RatingProfile

print(CGRateS_Obj.SendData({

"method": "APIerSv1.SetRatingProfile",

"params": [

{

"TPid": "RatingProfile_VoiceCalls",

"Overwrite": True,

"LoadId" : "APItest",

"Tenant": "cgrates.org",

"Category": "call",

"Subject": "*any",

"RatingPlanActivations": [

{

"ActivationTime": "2014-01-14T00:00:00Z",

"RatingPlanId": "RatingPlan_VoiceCalls",

"FallbackSubjects": ""

}

]

}

]

}))

print("GetTPRatingProfileIds: ")

TPRatingProfileIds = CGRateS_Obj.SendData({"jsonrpc": "2.0", "method": "ApierV1.GetRatingProfileIDs", "params": [{"TPid": "cgrates.org"}]})

print("TPRatingProfileIds: ")

pprint.pprint(TPRatingProfileIds)Okay, so at this point, all going well, we should have some data loaded, we’ve gone through all those steps to load this data, so now let’s simulate a call to a Mobile Number (22c per minute) for 123 seconds.

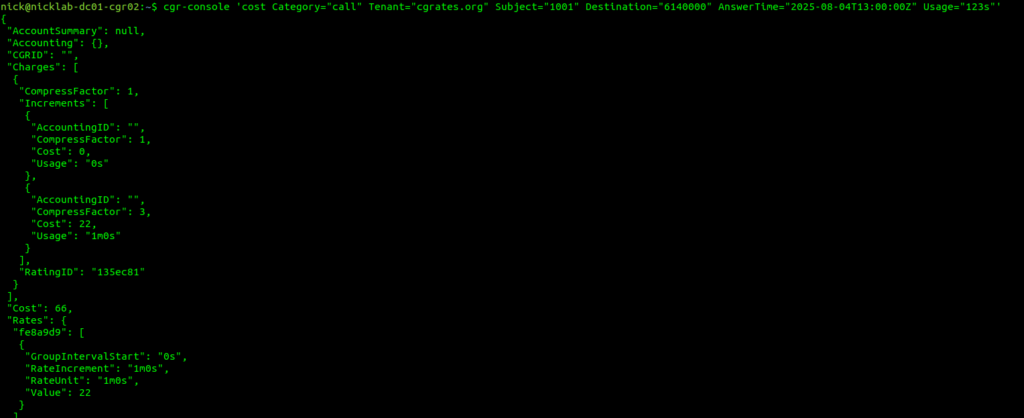

We can do this from the CLI:

cgr-console 'cost Category="call" Tenant="cgrates.org" Subject="1001" Destination="6140000" AnswerTime="2025-08-04T13:00:00Z" Usage="123s"'

We should get the cost back of 66 cents, as 3x 22 cents.

If that’s worked, breath a sigh of relief. That’s the worst done.*

As you may have guessed we can also check this through API calls,

print("Testing call..")

cdr = CGRateS_Obj.SendData({"method": "APIerSv1.GetCost", "params": [ { \

"Tenant": "cgrates.org", \

"Category": "call", \

"Subject": "1001", \

"AnswerTime": "2025-08-04T13:00:00Z", \

"Destination": "6140000", \

"Usage": "123s", \

"APIOpts": {}

}], "id": 0})

pprint.pprint(cdr)And you should get the same output.

If you’ve had issues with this, I’ve posted a copy of the code in GitHub.

We’re done here. Well done. This one was a slog.